Scleritis

is a severe, potentially sight threatening, inflammatory disease involving the

ocular surface. It has been be classified by PG

Watson et al,1 into anterior and posterior. Anterior scleritis can

be diffuse, nodular, necrotizing with inflammation (necrotizing), and

necrotizing without inflammation (scleromalacia perforans). Posterior scleritis2

is characterized by flattening of the posterior aspect of the globe, thickening

of the posterior coats of the eye (choroid and sclera), and retrobulbar edema.

The author states that the anatomical site and clinical appearance of

the disease at presentation reflected its natural history; majority of patients

remain in the same clinical category throughout the course of their disease.

Diffuse anterior scleritis had a lower incidence of visual loss (9%) than

either nodular scleritis (26%)

or necrotizing disease (74%), Patients with necrotizing scleritis were older

than patients in the other groups and more frequently had an associated

systemic disease than patients with either diffuse or nodular disease, 57%.3

According to another study, necrotizing

scleritis is associated with rheumatoid arthritis in most cases and less often

with SLE, Crohn's disease, Behcet's disease and gout.4 Diffuse and

nodular anterior scleritis is less often associated with any systemic disease.

An

underlying infectious etiology has been found to be relatively less common.

According to a study by Gonzalez et al5, out of 500 patients

presenting with scleritis, only 9.4% had an underlying infection with Herpes

virus infection (74%), tuberculosis (10%) and other infections in the remaining

14%.

An autoimmune deregulation in a genetically predisposed host

is presumed to cause scleritis. Inciting factors may include infectious

organisms, endogenous substances, or trauma. The inflammatory process may be

caused by immune complex–related vascular damage (type III hypersensitivity)

and subsequent chronic granulomatous response (type IV hypersensitivity).6

Ocular complications of scleritis, which cause visual loss

and eye destruction, appear as a result of the extending scleral inflammation.

These include peripheral ulcerative keratitis (13 – 14%), uveitis (about 42%),

glaucoma (12 – 13%), cataract (6 – 17%), and fundus abnormalities (about 6.4%).7.They

are most common in necrotizing scleritis, the most destructive type of

scleritis.

Despite

recent advances, its treatment remains a difficult problem. Systemic

immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents or

both is usually required to control the disease. Early therapeutic intervention

is important to prevent ocular complications and to minimize the potential

morbidity and mortality associated with underlying systemic disease. Systemic

corticosteroids in high dosage, either topical orally or in intravenous pulses,

are widely accepted as an effective form of treatment in patients with severe

scleritis.8 But this treatment is often associated with unacceptable

side effects and does not always control scleral inflamma-tion. Side effects

include adrenal suppression, vertigo, psychosis, pseudotumour cerebri, acne,

osteoporosis, myopathy and delayed wound healing.

The

addition of immunosuppressive agents in patients with severe scleritis improves

the ocular outcome and decreases the morbidity associated with systemically

administered corticosteroids.9 Azathio-prine, cyclophosphamide, and

cyclosporine have previously been reported to be effective and safe in the

management of severe ocular inflammation.10

Various studies have reported

the successful use of topical cyclosporine in the treatment of patients with a

variety of ocular inflammatory syndromes resistant to other immunosuppressive

regimens.11,12 Evidence obtained

from these studies supports the efficacy of topical cyclosporine treatment

through its immunomodulatory action, reversing inflammation of the ocular

surface and lacrimal glands. In the present study we report the

therapeutic effect of topical cyclosporine in the treatment of mild to moderate

scleritis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This is

a prospective case series of eleven consecutive patients with scleritis who

attended the out patients department of Mughal eye hospital, Lahore, from

January to December 2012. All cases were assessed by the same ophthalmologist.

A detailed history was taken and physical examination performed; distinction

was made between episcleritis and scleritis by the presence of eye pain, local

tenderness over the area of nodule in 6 cases and diffuse purplish hue in 5

cases of scleritis; the conjunctiva could be freely moved over that area and no

blanching of the lesion was achieved by a drop of 10% phenylephrine eye drops.

The cases presenting with episcleritis were excluded from the study. All

patients were graded to have an active anterior non-necrotizing scleritis of

mild to moderate severity without associated anterior or posterior uveitis.

Appropriate investigations including CBC, ESR, Rh – factor, serum ANCA, ACE,

chest X-ray and Mantoux test to exclude the presence of an associated

auto-immune or infectious disease; HLA auto-antibodies and C Reactive Protein

testing was not done due to economic constraints.

The

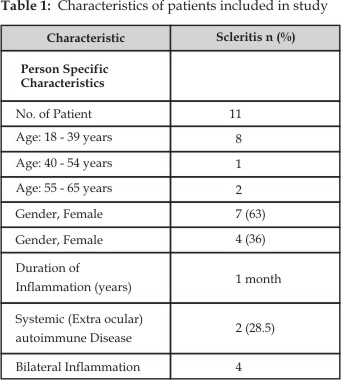

clinical features of the patients are summarized in (Table 1). There were seven

females between ages of 18 – 65 years and four males with the age of 45 years.

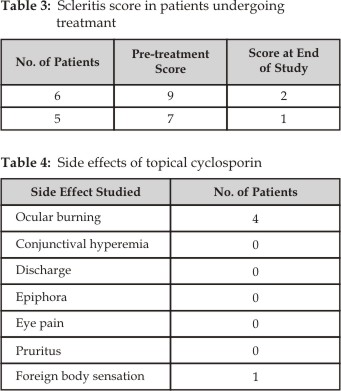

A subjective grading system, analogous to that previously described for

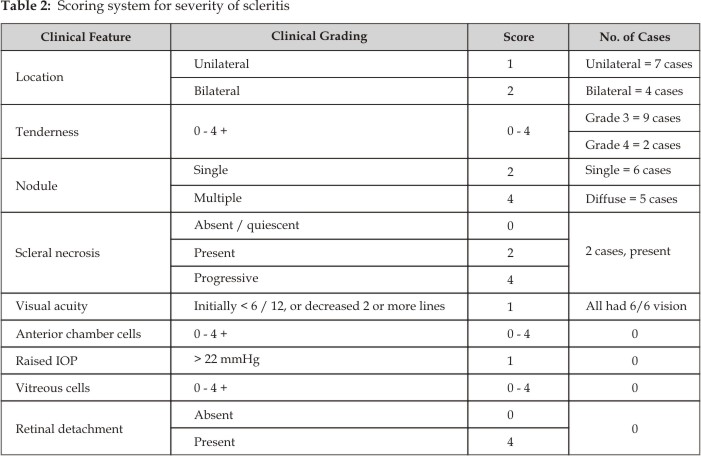

patients with uveitis and retinal vasculitis was used (Table 2).13 A

scleritis score was calculated when the patients first presented, then at each

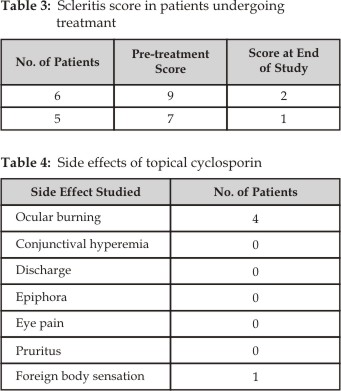

follow-up visit and at the end of the study (Table 3). Improvement was defined

as a decrease in the total score of greater than 2 and resolution at a total

score of less than or equal to 4.

All patients were fully

informed regarding the proper use and expected side-effects of topical

cyclosporine which was then started as 1% twice /day (freshly prepared from

cyclosporin capsules, 50 mg BIORAL; the water-miscible gel from 2 capsules

mixed with 5cc distilled water) along with preservative – free artificial tears

4 x / day (Biolan gel from Stullin Pharma, Germany). Treatment was started and

patients were reviewed weekly to note their subjective and objective

improvement. The therapy was conti-nued for 2 months in mild cases (Scleritis

score 6 – 7) and 3 months in moderate cases (Scleritis score = > 8). Then it

was gradually tapered by reducing the strength of Cyclosporin drops to 0.075%,

twice daily for 1 week, then once daily for one week, then on alternate day for

a week and then it was finally stopped.

RESULTS

Associated

active rheumatoid arthritis was found in only 2 female cases who were 60 years

old. No other systemic auto-immune or infectious disease was present in any

other case.

In all

cases, the subjective improvement of eye pain was noted in the first week of

therapy and objectively, reduction in scleral injection and tenderness improved

within 2 weeks of therapy. The scleritis scoring system is detailed in Table 2,

and Table 3 summarizes the scleritis score for each patient at presentation and

at four weeks after the commencement of treatment. In all patients

there was a significant decrease in the scleritis score at four weeks. This

decrease in the scleritis score was maintained over the subsequent observation

period. None of the cases developed scleral thinning, uveitis or a raised IOP

during or after the termination of therapy. The mean duration of treatment was

2 months in mild cases and 3 months in moderately severe cases. No recurrence

of scleritis was noted in 9 cases after stopping the therapy. Two cases (18%)

stopped therapy abruptly after one month only; in

them,

scleritis re-appeared which was again successfully controlled by starting the

same therapy and educating them regarding their proper use and weaning. No

recurrence of symptoms was noted in any case over one year follow-up after

stopping the therapy.

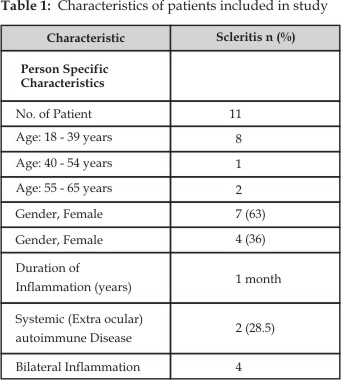

Cyclosporin eye drops were well

tolerated by all patients. Table 4 summarizes the side effects looked for in

the study. The only problem noted was stinging and a burning sensation on

instillation of drops which subsided after instilling preservative-free tear

drops after 10 minutes of instillation of cyclosporin eye drops. No other side

effect was noted.

DISCUSSION

All

eleven patients included in the study responded to the use of cyclosporine

(freshly prepared at our hospital pharmacy). A subjective improvement of eye pain

was noted within one week following the start of therapy and improvement of

scleral injection and tenderness was noted after two weeks of therapy.

It has

been increasingly recognized as an effective therapeutic agent in the

management of a variety of autoimmune diseases. It has been effectively used

topically in ocular surface disorders like vernal keratoconjunctivitis, dry eye

syndrome. Inflammatory eye disease, particularly uveitis, is often well controlled

by the regular use of systemic cyclosporin14.

Cyclosporin

represents the prototype of a new class of drug that appears to work, at least

in part, by acting at the level of cytokine production by immune cells.15 The

selective ability of cyclosporine to interfere with the action of interleukin-2

makes it an appropriate agent for the treatment of diseases mediated by T

cells. Although the immune-pathogenesis of scleritis is not fully understood,

it is believed to be due to immune complex mediated vascular damage to scleral

vessels, with the subsequent generation of a granulomatous reaction. T cells

have an essential role in the formation of such granulomas, and cyclosporine

may act in part by decreasing this component of the inflammatory response.

Multiple

studies on the efficacy of topical cyclosporine for treating inflammatory

ocular surface disorders have consistently shown a beneficial effect of the

drug.14,17 The immune-pathogenic mechanism is complex and involves

an IgE mediated immediate hypersensitivity response as well as a T cell

mediated immune reaction. Animal studies have shown that Cyclosporin has no

intraocular penetration; it concentrates on the ocular surface which enhances

its anti-inflammatory effect after long term use. Even after a year of regular

topical therapy, none to minimal blood concentration and in aqueous taps was

found in rabbits.

A large

study16 of 392 patients with non-infectious anterior scleritis

highlighted various therapeutic options available included NSAIDs, particularly

cox-2 inhibitors (but they result in cardiovascular side effects) in 144

(36.7%), oral or topical steroids in 29 (7.4%), immune modulatory drugs

(systemic cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate) in 149 (38.0%),

biologic response modifiers (BRM) in 56 (14.3%), and none (N = 14). Patients

with idiopathic diffuse or nodular scleritis with a low degree of scleral

inflammation or without ocular complications may respond to NSAIDs. Patients

with idiopathic diffuse or nodular scleritis with a high degree of scleral

inflammation may respond to steroids. Patients with diffuse or nodular

scleritis with associated systemic disease may respond to IMT or BRMs. Patients

with necrotizing scleritis may respond to IMT, mainly alkylating agents.

All these systemic therapies

are associated with many side effects. Similarly, topical steroids potentiate

corneo-scleral thinning, raised intra-ocular pressure and cataract. In

comparison, topical cyclosporin has minimal side-effects. Only precaution to be

used is that the beneficial affect is achieved after two weeks of therapy but

the immune process is still active and the therapy has to be continued for at

least two months and then gradually tapered, otherwise the disease flares up if

treatment is stopped abruptly and too early as seen in our two cases.

CONCLUSION

This study

highlights the fact that topical cyclosporine is a potentially useful drug in

the treatment of mild to moderate anterior scleritis; subjective and objective

clinical improvement is achieved within 2-3 weeks of regular usage. Hence, it

is an effective steroid- sparing agent. Unfortunately, its use is complicated

by frequent, mild side effects, like burning and stinging for a short while

after instillation of eye drops and may be associated with recurrence of

disease on suddenly stopping the therapy.14 Patients need to be

informed and educated regarding its appropriate use.

To avoid recurrence of the

disease, therapy has to be continued for at least 2 – 3 months and then

gradually tapered. Another problem with cyclosporine eye drops is that they

have to be made fresh, without preservatives and have a shelf life of one week

only. Despite these limitations we consider that topical cyclosporine is a

useful drug in the management of mild to moderate scleritis, and has a high

therapeutic value in the treatment of this disease.

Author’s

Affiliation

Dr. Sameera Irfan

Mughal Eye Hospital (Trust)

Lahore

Dr. Harris Iqbal

Mughal Eye Hospital (Trust)

Lahore

REFERENCES

1.

Tuft SJ, Watson PG. Progression

of scleral disease. Ophthalmology. 1991; 98: 467-71.

2.

Machado Dde O, Curi AL, Fernandes RS, Bessa TF, Campos WR, Oréfice

F. Scleritis: clinical

characteristics, systemic associations, treatment and outcome in 100 patients.

Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2009; 72: 231-5.

3.

Riono

WP, Hidayat

AA, Rao

NA. Scleritis: a clinicopathologic study of 55 cases. Ophthalmology.

1999; 106: 1328-33.

4.

Sousa JM, Trevisani VF, Modolo RP, Gabriel LA, Vieira LA, Freitas DD.

Comparative study of ophthalmological and serological manifestations and

the therapeutic response of patients with isolated scleritis and scleritis

associated with systemic diseases. Arq Bras

Oftalmol. 2011; 74: 405-9.

5.

Sainz de la Maza M, Jabbur NS; Foster CS. Severity of scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101: 389-96.

6.

Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS, Jabbur NS. Scleritis associated with systemic vasculitic

diseases. Ophthalmology 1995; 102: 687-92.

7.

Durrani K, Zakka FR, Ahmed M, Memon M, Siddique SS, Foster CS. Systemic therapy

with conventional and novel immunomodulatory agents for ocular inflammatory

disease. Ophthalmol. 2011; 56: 474-510.

8.

Raizman M. Corticosteroid therapy of eye

disease. Fifty years later. Arch Ophthalmol.

1996; 114: 1000-1.

9.

Sainz de la Maza M,

Molina N,

Gonzalez-Gonzalez

LA, Doctor PP,

Tauber J,

Foster CS. Scleritis therapy. Ophthalmology.

2012; 119: 51-8.

10.

Carrasco

MA, Cohen

EJ, Rapuano

CJ, Laibson

PR. Therapeutic decision in anterior scleritis:

our experience at a tertiary care eye center. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2005; 28: 1065-9.

11.

Machado

Dde O, Curi

AL, Fernandes

RS, Bessa

TF, Campos

WR, Oréfice

F. Scleritis: clinical characteristics, systemic associations,

treatment and outcome in 100 patients. Arq Bras Oftalmol.

2009; 72: 231-5.

12.

Gumus K, Mirza GE, Cavanagh HD, Karakucuk S. Topical cyclosporine A as a steroid-sparing

agent in steroid-dependent idiopathic ocular myositis with scleritis: a case report and review of

the literature. Eye Contact Lens. 2009; 35: 275-8.

13.

Foster CS, Forstot SL, Wilson LA. Mortality rate in rheumatoid arthritis patients developing

necrotizing scleritis or peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1984;

91: 1253-63.

14.

Utine CA, Stern M, Akpek EK. Topical Ophthalmic Use of Cyclosporine A. Immunology and Inflammation. 2010; 18: 352-61.

15.

McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D.

Current concepts in the management of scleritis. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol. 1988;

16: 169-76.

16.

Hillenkamp J, Kersten A, Althaus C, Sundmacher R. Cyclosporin A therapy in severe anterior scleritis. 5 severe courses without verification of associated

systemic disease treated with cyclosporine

A. Ophthalmology. 2000; 97: 863-9.

17.

Kaçmaz RO, Kempen JH, Newcomb C, Daniel E, Gangaputra S,

Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Suhler EB, Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Clarke GA, Foster

CS. Cyclosporine

for

ocular inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology.

2010; 117: 576-84.