Trauma

to the eye may result in various injuries including presence of blood in the

anterior chamber without perforation of the eye. Closed-globe traumatic

hyphaema may cause diverse complications including associated traumatic uveitis

which generally accompanies the initiating trauma, secondary haemorrhage,

corneal blood staining, synechia formation, and ocular hypertension /

secondary glaucoma.1,2 Aim of management is primarily to prevent

these sight-threatening complications from occurring, or if that fails, treat

them if they arise. Treatment of complications when they arise is fairly

straightforward, but preventing them from occurring is a challenge, arising

from difficulty in predicting who among patients will develop any of these

complications. The result is differences of approach among ophthalmologists and

thus to different management practices. These practices and associated

controversies include advantage of ancillary measures like hospitalization, bed

rest with restriction of activities versus ambulation and at-home treatment;3,4

utility of padding the affected eye or both eyes;5.6 and the place

and usefulness of various medications topical, oral and systemic in preventing

complications.

Numerous studies disclose

conflicting results as to benefit derivable from various medications commonly

used in traumatic hyphaema1,6-8 resulting in many ophthalmologists

in parts of the world either commonly using and recommending them, while others

do not.3,5,6,9,10 Surveys of ophthalmologists in Texas11,

USA disclosed absence of agreement in virtually all aspects of management; and

in the UK,12 divergent views on appropriate medications were

expressed by ophthalmologists. This study is designed to disclose views and

practices of Nigerian ophthalmologists concerning the various medications they

use routinely in uncomplicated closed-globe traumatic hyphaema so as to

determine the dominant views among them in this regard. In the absence of a

multi-center case-control study it is hoped the results obtained from a broad

base of practitioners would act as a guide in the Nigerian and similar

environment.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A convenience sampling of

Nigerian ophthalmologists who attended the afternoon scientific session on the

16th September 2008 of the annual general congress of the ophthalmological society of Nigeria (OSN) at

Ile Ife in by means of a semi-structured pre-tested questionnaire. Responses

were analyzed with SPSS 11 software.

RESULTS

One

hundred and seven questionnaires were distributed; 101 were retrieved, but 8

were discarded because filling was substantially incomplete, resulting in 93

used for this analysis.

Respondents were from 42 eye

care centers. Of these 93 practitioners, 9 ophthalmologists practice in 4

private eye care facilities and 84 represented 38 public hospitals-tertiary and

secondary. Public eye care centers captured in the study is estimated to

constitute about 75% of such institutions in Nigeria. Among the practitioners,

92.5% declared that resort to surgery was infrequent in traumatic closed globe

hyphaema, and they found non-surgical means usually adequate for preventing and

treating of most complications. Results are presented in tables 1-3, and in Fig.

1.

DISCUSSION

ANCILLARY MANAGEMENT

Complications

of traumatic hyphaema as depicted in figure 1 can result in loss of vision, and

treatment is aimed at preventing this complication occurring or reducing their

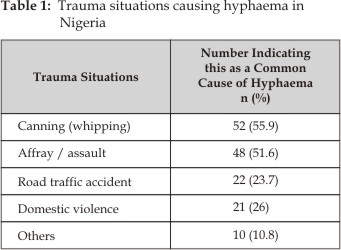

potential for causing loss of vision. The specific causes of traumatic hyphaema

in Nigeria as depicted in table 1 do not tend to be more amenable to

non-surgical treatment as far as we know.

Part of

traditional management of hyphaema patients involved hospital admission and

restriction of activities in the form of bed rest. The patient was required to

lie in bed with the head and shoulder raised to 30 45 degrees and both eyes

were covered with a rigid shield. Medications used included topical

cycloplegics and glucocorticoids, oral sedatives and sometimes prednisone

tablets 2. These measures were thought to be useful in preventing secondary

haemorrhage: activity restriction to reduce stress induced raised venous

pressure, binocular patching to prevent accommodative and pupillary activity

that might induce dislodgement of clot blocking the torn vessel and result in

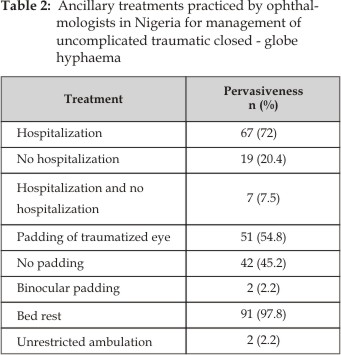

secondary haemorrhage. It is apparent from table 2 that Nigerian

ophthalmologists in large measure still practice these methods. This is because

of its claimed benefits and the pressure of tradition.

The value of head up position

is to better estimate level of blood and thus classify the hyphaema, determine

if it is decreasing or increasing, facilitate drainage from wider lower

trabecular meshwork, and to have a hyphaema level below pupillary level for

ease of ophthalmoscopy and faster recovery of vision for visual acuity

assessment.13 This appears more of an empirical treatment since the

head-up position is utilized in all grades of hyphaema-those with fluid level

below the pupil, and even in the presence of clots. Unfortunately if the

inferior angle is the part damaged, the head-up position is valueless, and

could in fact be deleterious as the rate of decrease of hyphaema may be

compromised.

Fig. 1: (Okosa and Onyekwe) Complications observed by

Nigerian ophthalmologists on patients with traumatic hyphaema

Although

studies with regards to hospitalization, padding and bed rest were found by

investigators not to influence complication rate, duration of hyphaema and

final visual acuity3,4,5,6 many ophthalmologists in many

institutions still practice and recommend them to varying degrees. These

different approaches are reflected among Nigerian ophthalmologists: 97.8%

insist on bed rest with head-up position, although 72% routinely admit all

patients with closed-globe hyphaema on initial contact.

Reason

for seeming preference for hospitalization is that all patients with hyphaema

require daily examination and monitoring of intra-ocular pressure and other

complications; and it is not possible to monitor for these with patient at

home. Compliance with bed rest and medication in a patient at home cannot be

monitored. Patients may find it inconvenient, or sometimes impossible, to come

from far distances daily, and at the time required for necessary follow-op,

making it seem prudent to admit them.

Padding of affected eye is not

as widespread as bed rest or hospital admission as uniocular patching is

deployed by 54.8%; as against 45.2% who do not pad at all, while 2.5% pad both

eyes. Explanation of the seeming preference for eye padding is to shield the

injured eye and prevent further trauma and secondary haemorrhage although

studies have not demonstrated any differences in complication rate or

requirement for surgery between patients who had eye pad and others who do not5,6.

Topical Medications

Table

3: Drugs routinely used by Nigerian ophthalmo-logists, and their

frequency for management of traumatic non-penetrating hyphaema

|

Glucocorticoid eye drops/ ointment |

81 (87.1) |

|

Atropine and other cycloplegics |

75 (80.6) |

|

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAI) tablets |

55 (59.1) |

|

Gluco-corticoid eye drops + cycloplegic agent + CAI |

47 (50.5) |

|

Vitamin C tablets 100 mg tid |

10 (10.8) |

|

NSAID eye drops + tablet |

3 (3.2) |

|

Sedatives: diazepam 5 mg bid for adults |

3 (3.2) |

|

Acetaminophen tablets 500mg -1000mg tid for adults |

2 (2.2) |

|

Antibiotic eye drops |

2 (2.2) |

|

Pilocarpine eye drop 1% |

1 (1.1) |

|

NSAID eye drop |

1 (1.1) |

|

Amino-caproic acid |

1 (1.1) |

|

No routine medication |

8 (8.8) |

A preponderant majority (91.4%)

of Nigerian ophthalmologists, as displayed in Table 3, routinely use single or

combination of medications as only 8 of the 93 sampled do not use any

medication in uncomplicated hyphaema. Cycloplegic and glucocor-ticoid eye drops

the most commonly used combination, are deployed with the expectations that by

stabilizing the iris blood vessels, they will control anterior uveitis

resulting from the trauma or presence of blood in the anterior chamber, which

inflammation was both a source of discomfort to the patient, and thought to

predispose to secondary haemorrhage14. Additionally these

medications prevented synaechia formation in hyphaema of long duration; and pupillary

dilatation caused by mydriatics allowed an earlier visual acuity assessment in

clearing hyphaema. The plethora of practices no doubt reflects effect of

diverse and conflicting reports by investigators in this matter. For example

Oksala found topical steroid and cycloplegics reduced re-bleed rate in addition

to treating associated anterior uveitis,14 but a study in Kuwait

City did not find any difference in resolution of traumatic hyphaema, the

complication rate or requirement for surgery among three groups of patients:

those treated with combination of topical cycloplegic agent with

corticosteroid; those treated with corticosteroid eye drops only; and those

treated with placebo in the form of artificial tears.6 It is not

known what factors are responsible for differing effects of these drugs in

these different population groups. Could it be related to diet, habit, blood

group, tissue types, and mechanism of injury? Until these questions are

answered, it appears the practice among Nigerian ophthalmologists is to err on

the side of safety by administering these drugs. It might be argued that

cycloplegics by bunching the iris towards the anterior chamber angle may impede

rate of drainage and raise the IOP, and by its weakening effect on the iris

muscle result in more frequent incidences of re-bleeding; or that miotics would

have the opposite effect. However Rakusin found no difference in complication

rate and resolution of hyphaema among patients treated with miotics,

mydriatics, both or none.7 Conclusion from these studies is that

ancillary and medical treatments have not been conclusively proved to influence

the spontaneous resolution of hyphaema, reduce its complication rate or

decrease need for surgery. This not withstanding routine use of topical

cycloplegic and glucocorticoid drugs in this condition by a vast majority of

Nigerian ophthalmologists is a practice shared by many, but by no means all, of

their contemporaries in other places.1,3,5,8 Reasons for persistence

in use of these medications prophylac-tically include that old practices die

hard especially if they are not demonstrably harmful, and could cause some

good. Besides it is probably more satisfying for the patient and the doctor to

be seen as doing something instead of not treating the patient. Very few

ophthalmologists would be able to send a patient with uncomplicated closed globe

hyphaema home, without padding, no bed rest, and no drug despite reports that

these measures are probably not helpful. Perhaps legal and ethical

consideration in the present situation of uncertain knowledge concerning

possible benefits compel practitioners to offer probably unnecessary treatment in

this condition corresponding to the assertions of Romano and Phillips.10 Why do the few (8.6%) found in current study

not give any medications routinely in uncomplicated hyphaema? The reason is

probably because it would appear as bad science, pointless, and not

evidence-based to subject patients to expenses and inconvenience of treatment

without demonstrable good as the outcome.

Oral Medications

Ophthalmologists

in the UK were unanimous in agreeing on absence of any place for use of

systemic medications in uncomplicated hyphaema12 except for carbonic

anhydrase inhibitors (CAI) which were used by 54% of them for adult patients

with an IOP of above 25 mm Hg. This contrasts with situation among Nigerian

ophthalmologists in which 73% use at least one oral medication routinely (table

3). Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, is commonest oral medication, and are used

routinely by 59.1% of Nigerian ophthal-mologists as a pro-active measure in all

patients with hyphaema, to prevent secondary glaucoma, especially in large

volume hyphaema. It is not clear why topical pressure lowering agents are not

preferably used rather than oral CAI as some of them are quite affordable,

available and have less adverse reactions.

Use of

NSAIDs however is not popular, being employed by only four ophthalmologists- as

tablets by three (3.2%) and as tablet and topically by one (1.1%). The

rationale for its use appears to be to prevent clot formation and quicken

resolution time of hyphaema. However its efficacy in these has not been demons-trated

in any study, to our knowledge, but rather its use in hyphaema has been

associated with re-bleeding.2 In present survey three of the four

practitioners (75%) who routinely used NSAIDs as oral medication in

uncomplicated hyphaema reported secondary haemorrhage as a frequent

complication, one reported a frequent need for surgical evacuation of hyphaema;

only 36.7% of those who do not use NSAIDs reported re-bleeding as a frequent

complication.

Oral fibrinolytic agents

-amino-caproic acid (ACA) and tranexamic acid are in the main not used,

probably because of lack of availability, cost and perhaps contradictory, and

adverse effects reported by some investigators, and bias of practitioners

against them.2,5,15,10 Topical ACA is currently not available in Nigeria

to the authors knowledge. Use of oral sedatives, acetaminophen tablets and

topical antibiotics are also not as popular as use of oral carbonic anhydras

inhibitors or topical glucocorticoids and atropine as displayed in Table 2.

CONCLUSION

Differences in both ancillary

and medical treatment, found among Nigerian ophthalmologists in management of

closed globe traumatic hyphaema reflect situation among practitioners in

other parts of the world because of absence of clear cut protocol for

management derived from controlled trials. Difficulty in devising a controlled

trial in this condition include problem of adequately matching patients and

ethical considerations of study protocols in which no treatment controls are

utilized10. Many outcome studies of traumatic hyphaema management

were noted as flawed due to inadequate protocol and bias10,16

limiting their utility and validity as guide. The best that can be done is to

get data from a wide base of trained observers and practitioners who manage

this condition for a closer approximation to a valid guideline. This we have

attempted to do in this study resulting in some suggestions and recommendations

to act as a guide, although the application in some situations may need

modification as is usually advised in management of probably all medical

conditions.

Authors Affiliation

Dr. Okosa Michael Chuka

Senior Lecturer, and Former Head, Department of Ophthalmology

Nnamdi Azikiwe University and Consultant Ophthalmologist and former Head,

Guinness Eye Centre Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital; Onitsha,

Nigeria

Dr.

Onyekwe Lawrence Obizoba

Consultant Ophthalmologist Department of Ophthal-mology, Nnamdi

Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital and Guinness Eye Centre Onitsha, and Professor

of Ophthalmology, College of Health Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi

campus, Nigeria

Dr. Anajekwu Cosmas Chinedu

Resident

Doctors Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi campus, Nigeria

Dr. Mbakigwe Chidi Fidelis

Resident Doctors Nnamdi Azikiwe

University, Nnewi campus, Nigeria

REFERENCES

1.

Walton W, Van Hagen S, Grigorian R, Zarbin M. Management of traumatic hyphaema. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002; 47:

297-334.

2.

Sheppard JD, Crouch ER, Williams PB, Crouch ER, Rastogi S,

Garcia-Valenzuela E. Hyphaema. http:// emedicine.medscape.com/article/1190165-overview.

3.

Luksza L, Homziuk M, Nowakowska Klimek M, Glasner L,

Iwaszkiewicz Bilikiewicz. Traumatic hyphaema

caused by eye injuries. B. Klin Oczna. 2005; 107: 250-1.

4.

Shiuey Y, Lucarelli MJ.

Traumatic hyphema: outcome of outpatient management. Ophthalmol. 1998; 105:

851-5.

5.

Fareed A, Warid M, Al Mansouri F. Management of non-penetrating traumatic hyphema in ophthalmology

department of HMC review of 83 cases. Middle East J of Emergency. 2004; 4: 1.

6.

Behbehani AH, Abdelmoaty

SMA, Aljazaf A. Traumatic hyphema Comparison

between different treatment modalities. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2006; 20: 164-6.

7.

Rakusin W: Traumatic hyphema. Am J Ophthalmol 1972; 74: 284-92.

8.

Papaconstantinou D, Georgalas I, Kourtis N, Karmiris E,

Koutsandrea C, Ioannis Ladas I, Georgopoulos G. Contemporary aspects in the prognosis of hyphaema. Clin

Ophthalmol. 2009; 3: 28790.

9.

Yasuna E. Management of Traumatic

Hyphaema. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974; l 91: 190-91.

10.

Romano PE, Phillips PJ.

Traumatic hyphaema: a critical review of scientifically catastrophic history of

steroid treatment therefore; and a report of 24 additional cases with no

re-bleeding after treatment with the yasuna systemic steroid, no touch

protocol. Bin Vis Strab. 2000; 15: 187-96.

11.

Kelly JL, Blanquist PH.

Management of traumatic hyphema in Texas. Tex Med. 2002; 98: 56-61.

12.

Little BC, Aylward BW. The medical management of traumatic hypheama: a survey of opinion

among ophthalmologists in the UK. J Roy Soc Med. 1993; 86: 458-9.

13.

Earl R, Crouch ER Jnr.

Management of traumatic hyphaema: therapeutic options. J Paedtr Ophthlmol Strab.

1999; 36: 238-50.

14.

Oksala A. Treatment of traumatic

hyphaema. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967; 51: 315.

15.

Fong LP. Secondary hemorrhage in

traumatic hyphema. Predictive factors for selective prophylaxis. Ophthalmol.

1994; 101: 1583-8.

16.

Hopewell S, Loudon K, Clarke MJ, Oxman AD, Dickersin K. Publication bias in clinical trials due to statistical

significance or direction of trial results. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews 2009, Issue 1.