Orbital masses can be inflammatory, infectious and

neoplastic in origin. In orbital space, they present with overlapping clinical

manifestations. The slow growth of a solitary, discrete mass is usually

suggestive of tumor. Fungal infections of the orbit are usually seen in immune

compromised state1. But here, we report a case of orbital fungal

granuloma in a young female who was immune-competent and managed

satisfactorily.

CASE

REPORT

A 20 years old unmarried female,

presented to our tertiary care hospital with painless progressive non-axial proptosis of the left eye for the last 1 year. She had

outward deviation of the left eye with no double vision. She had no visual

complaints, no complaints of redness, discharge and photophobia. There was no

history of trauma, surgery, systemic illness, lymphadenopathy and nose or

throat infection. She had no fever and reported no change in appetite or

weight. Past medical and surgical history was unremarkable. She reported no

evidence of a disease causing immune suppression. Family history was

unremarkable.

On examination, visual acuity was 6/6 unaided in both eyes.

There was non-axial proptosis of 23 mm of the left

eye on Hertels exophthalmometer,

which increased slightly on Valsalva maneuver. She had an exotropia

of 45 degrees on cover test. The dystopia was measured to be 5 mm outwards and

5 mm upwards in the left eye (Fig 1). There was no complaint of diplopia. Bruit

and pulsation were absent. Anterior segment

examination was normal.

Fig. 1: proptosis and exotropia

of left eye on initial presentation.

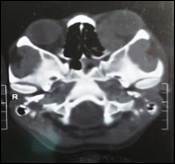

Fig. 2: CT scan coronal and axial view showing mass involving

medial rectus.

Laboratory

findings revealed normal blood count, blood glucose level, PT and APTT.

Ultrasound abdomen and x-ray chest were of no significance. Computed tomography

of orbits and PNS revealed, diffuse thickening of medial rectus (Fig. 2). Rest

of the left eye appeared normal. Right eye, nasal cavity and sinuses were

within normal limits.

MRI orbit

showed thickening of medial rectus muscle and involvement of retrobulbar fat with proptosis of

left eye and compression of optic nerve Fig. (3). Brain appeared normal.

Fig. 3: MRI axial view showing the mass invading the medial rectus.

These findings gave the impression of a mass involving the

medial rectus. Surgical excision was performed under general anesthesia. Lynch Howarth approach was used. The excised mass which was

yellowish in colour unlike the medial rectus on naked

eye examination was excised and wound closed with 6/0 vicryl

(Fig 4). But the medial rectus tendon was forming the anterior end of the mass

which suggested that the muscle had lost its characteristic appearance due to

pathological changes. The tendon was identified and separated from the sclera

with a muscle hook before excision. Biopsy specimen was sent for histopathology

(Fig. 5).

Fig. 4: The tumour being removed.

Fig. 5: Biopsy specimen.

On a follow up

examination, 2 weeks after surgery, proptosis was

decreased to 20 mm. Optic disc, anterior and posterior

segments were within normal limits. Intraocular pressure was 16 mm Hg. Inward

eye movements were restricted (grade -4), but normal on superior, inferior and

lateral gaze (Fig. 6). There was no diplopia.

Fig. 6: Left exotropia with absent

abduction at 2 weeks Post op.

Histopathology report showed fibro-connective

tissue with granulomatous inflammation. Granulomas were composed of aggregates

of epitheloid cells, surrounded by collar of

lymphocytes and histiocytes with multiple

multinucleated giant cells within the granuloma. Scattered eosinophills

were also identified. Few granulomas showed septate

hyphae. Histochemical stains were positive for fungal

organisms.

Fig. 7: Post op CT showing residual fungal granuloma.

The proptosis

decreased after 2 weeks, but there was no movement of left eye on medial gaze,

due to absent medial rectus muscle and exotropia of

45 degrees was seen. Post op CT and MRI scans were carried out. They showed

residual fungal granuloma (Fig. 7). Patient was prescribed tablet Itraconazole(

sporonox) 100 mg twice a day for 3 months. After 3

months, CT and MRI were again carried out, which showed no recurrence of fungal

granuloma.

Cosmetic squint correction was done for the large angle exotropia by performing Hummulsheim

procedure. In this procedure, there was full tendon transfer of superior and

inferior recti to the medial rectus. A Jenson procedure involving split tendon

transfer could be done but we opted for full tendon transfer due to the very

large angle exotropia. Lateral rectus recession was

not feasible due to the absence of medial rectus which would pull it medially

after surgery. Post-op examination after 4 weeks showed improvement of exotropia on primary position to 30 degrees (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Residual small angle exotropia of

left eye at 4 weeks post op.

DISCUSSION

In adults, primary orbital tumors are

lymphoid tumors, cavernous hemangioma, meningioma, neurofibroma and schwannoma. Most

common presentations are proptosis and exophthalmos.

Infectious and inflammatory process has acute onset as compared to tumors,

which has slow onset. In the presented case fungal granuloma developed in an

immune competent patient over a period of 1 year with no acute symptoms except proptosis.

Orbital infections occur due to spread

of infections from paranasal sinuses or direct from

trauma and surgery. Most common organisms are bacteria, while viral and fungal

infections are rare. Organisms causing fungal infections include aspergillus. Mucormycosis and Cryptococcus species2. Aspergillus

granuloma is the most commonly reported intracranial granuloma among fungal

granulomas3. It is the common causative fungal organism of

intracranial fungal mass lesion accounting for approximately 56% to 69%3.The

estimated annual incidences of systemic invasive fungal infections caused by Aspergillus species are 12-34%4. The estimated

incidence of fungal infection is 4-6% of CNS involvement5.

Fungal infections commonly occur in immune compromised state like diabetes

mellitus (37%)6, AIDS or excessive steroid

use. The common sites of involvement are nasal cavity (10%), brain with sinonasal (36.6%) and nose and orbital cavity (53.3%)7. Some of the reports shows

that the fungal infections can present as optic neuritis8. It can present

in the form of sub periosteal abscess9. Optic

neuropathy8, orbital apex syndrome10 and orbital

tuberculosis with coexisting fungal granulomas11.

To assess the orbital disease, MRI

imaging is preferable because it gives full detail of the soft tissue

structures. The MRI findings are characteristics in fungal granuloma. These

include a mass lesion producing hypo-intense or iso-intense

lesion on T1 weighted and hypo intense lesion on T2

weighted images12.

In our case, MRI findings of fungal

granuloma on T1 weighted images were iso-intense

while they were hypointense on T2 weighted

images, which in literature are characteristic of aspergillus

fungal granuloma. Its non-tender and non-inflammatory nature caused it to be misdiagnosed

as tumor. So, fungal infections should always be kept in differentials of such

solitary orbital masses.

Surgery is important both for initial diagnosis and for

excision of granuloma, allowing for a better treatment efficacy of systemic

antifungal agents like Amphotericin B and Itraconazole

100-400 mg twice a day for 3 months.

CONCLUSION

Orbital fungal granuloma may affect immune competent healthy

patients as well as immune compromised patients. Main stays of treatment are

surgical debridement and systemic antifungal therapy. Early diagnosis can

prevent the extensive surgical intervention.

Authors Affiliation

Dr. Saher Khalid

PGR Eye

Unit 2

lahore General Hospital

Lahore

Dr.

Mohammad Moin

Professor

Ophthalmology

Eye

Unit 2

Lahore

General Hospital

Lahore

REFERENCES

1.

Zafar MA, Waheed

SS, Enam SA. Orbital aspergillus infection

mimicking a tumor: a case report. Cases journal. 2009; 2: 7860.

2.

Hershay BL, Roth TC. Orbital infections. Semin ultrasound CT

MR 1997; 18: 448-59.

3.

Sundram C, Umabala P. Pathology of fungal infections of

central nervous system: 17 years experience from Southern India. Histopathology.

2006; 49: 396-405.

4.

Pfaller MA. Pappas PG. invasive fungal pathogens, current epidemiological

trends. Clinical infectious disease. 2006; 43: 3-14.

5.

Kethireddy S, Andes D. CNS pharmacokinetics of antifungal agents. Expert Opinion on Drug

Metabolism and Toxicology. 2007; 3: 573-81.

6.

Finn DG. Mucormycosis

of paranasel sinuses. Ear Nose Throat J. 1998; 67:

813-16.

7.

Javadi M. Fungal infection of the sinus and anterior skull base. Med J

Islam Repub Iran. 2008; 22: 137-40.

8.

Mafee MF, Goodim J. optic nerve sheath meningiomas.

RadiolClin North Am. 1999; 37: 37-58.

9.

Spoor TC, Hartel

WC. Aspergillosis presenting as a corticosteroid responsive

optic neuropathy. J Clin Neuroophthalmol.

1982; 2: 103-7.

10.

Matsou T, Notohara K. aspergillosis causing bilateral optic neuritis and

later orbital apex syndrome. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005; 49: 430-1.

11.

Reddy SS, Penmmaiah

DC.

Orbital tuberculosis with coexisting fungal infection. Surg

NeurolInt. 2014; 5: 32.

12.

Siddiqui AA, Bashir SH. Diagnostic MR imaging features of craniocerebralaspergillosis of sino

nasal origin in immune competent patients. Acta Neurochir. 2006; 148: 155-66.