Ocular trauma is an

important cause of visual impairment1 and a leading cause of

preventable uni-ocular blindness world wide.2

It is an important cause of utilization of

ophthalmic service resources.3

It has been

rated as the third most common ophthalmic indication for hospitalization

in the United States.4 Even

the most minor injuries can cause pain and discomfort, lost wages and health

care expenses.5 In Nigeria,

ocular injuries are still rampant6. There are varying pattern and

causes of ocular injuries from one country to another and even within regions in

the same country. Many studies however report higher prevalence of eye injuries

among males when compared with their female counterparts.7,8 Most cases of trauma are avoidable.9 Visual outcomes following eye injuries vary

from full recovery to complete blindness with physical and psychological loss

and enormous costs to society.10 Blindness from trauma could

be as a result of the direct impact of the trauma as well as the

appropriateness and timeliness of the treatment technique utilized. Knowledge

of the pattern and causes of eye trauma in this environment will help to know

the common causes as well as get the facts necessary for health education

materials for planning of preventive actions as well as need to seek early and

appropriate intervention for eye injuries when they occur.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A prospective observational study of all consecutive cases of

trauma was seen at an eye care centre over a 15 month period from January 2012 to March 2013.

Eighty five patients presenting with eye injuries were included. This included

patients of all ages with acute injury to one or both eyes. Patients who had

healed ocular trauma or had been given surgical treatment for trauma elsewhere

were excluded from this study. A

questionnaire was administered to each respondent by face to face interview.

The interview was conducted in English language, with language translation into

Yoruba when necessary. The interview elicited information on the following:

Demographic data, affected eye, agent of injury, activity at time of injury,

duration before presentation, associated injury, medication used, source of

referral and protective spectacle wear at the time of injury. All the patients

had their visual acuity checked with the Snellens

chart (or illiterate E chart) placed at 6 metres.

Visual acuity in the better eye of 6/6 6/18 was considered to be normal; <

6/18 - 6/60 was classified as visual impairment and < 6/60 3/60 as severe

visual impairment while visual acuity less than 3/60 was classified as

blindness. Eye examination was carried out with the aid of a pentorch, a slit lamp biomicroscope

and a direct ophthalmoscope. Dilated examination with indirect ophthalmoscopy

was carried out on those with poor view from hazy media. Ocular ultrasound was

done for those with closed globe injuries when the view of the fundi was

precluded by hazy media. Intraocular pressure check was conducted with the aid

of goldman applanation tonometer for cooperative patients with closed

globe injuries.

Data

was recorded and all statistical analyses were performed with commercially available

computer program, Statistical Package

for Social Science (SPSS) version 13.0. Data are expressed as Mean ±

Standard Deviation (SD) and frequency expressed as a percent-age. The

relationships between categorical data were analyzed using Chi- square (X2)

test. At the adopted confidence level of 95%, P value of 0.05 (i.e. 5%) or less

was considered to be significant. Yatess corrected chi-square and the

appropriate Fishers exact p value were used where the value of any cell was

less than 5.

RESULTS

Ninety one eyes of eighty five

patients were seen during this study period with their ages ranging from 4

years to 78 years and a mean age of 31.7 ± 19.7 years. This constituted 3.8% of

all the outpatients seen in the clinic during the study period. Eighteen

(21.2%) were children while 67 (78.8%) were adults with 45 (53.1%) of these

aged between 20 60 years. There were more males than females across the age

groups with a male to female ratio of 2:1. The affectation was unilateral in 79

patients (93%) (39 on the left and 40 on the right) and

bilateral in 6 (7%). There was associated injury involving the head in 1

patient (1.2%), and face in 8 (9.4%). There were no associated injuries in

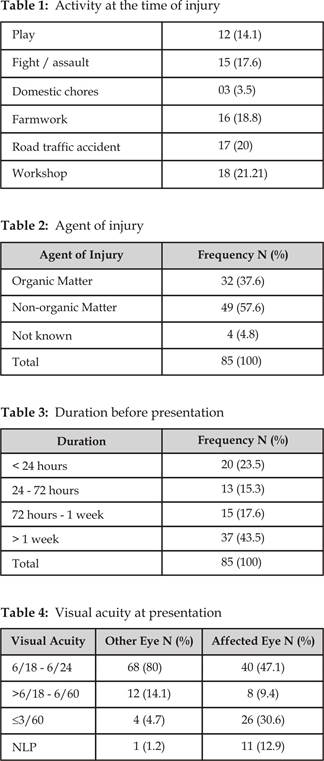

76(89.4%). The activities at the time of injury are as shown in Table 1 below.

Injuries were work-related in 34 (40.0%). Open globe injuries occurred in 11

(12.9%) of the subjects while a larger percentage 74 (87%) had closed globe

injuries. There were no cases of retained intraocular foreign bodies. Majority

84 (98.8%) of the patients were not wearing protective eye spectacle at the

time of injury. The commonest agent of injury was non-organic matter in 49

(57.6%) of the subjects, another 32 (37.6%) was due to injury from organic matter

as shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows that only 20 (23.5%) of the patients

presented within 24 hrs of injury. Visual acuity at presentation was less than

6/60 in 37 (43.5%) of the affected eyes of the patients. Other details are as

shown in Table 4. Majority of the patients 60 (70.6%) self

presented to the hospital without any referral letter. The significant

eye findings at presentation are as shown in Table 5. The types of medications

applied to the eyes before presentation are as shown in Figure 2. 58 (68.2%) of

the patients had medical intervention while 27 (31.8%) had surgical

intervention.

DISCUSSION

Traumatic

eye injuries have been found to be a common phenomenon in developing countries

like ours11. They are an important cause of utilization of ophthalmic

service resources.4,12 In this study, there

were 2 times more males than females. This finding is in line with previous

reports stating that there is a higher involvement in trauma among the male

gender because the males are more active and engage in a lot more outdoor and

risk ladened activities than their female

counterparts.5,13,14 More than half of the

study population were aged between 20 60 years. These are mostly people in

the active and economically productive age similar to the findings by some

other authors.5,15-17 The greater

percentage of unilateral cases than bilateral suggests a reason why trauma has

been found to be the commonest cause of unilateral blindness. There was no

left-right preponderance in the eye affected contrary to

studies where the left eye has been found to be more commonly affected compared

with the right.14.18.

Table

5: Examination

findings at presentation

|

Lid laceration |

5 (5.9) |

|

Subconjunctival

hemorrhage |

13 (15.3) |

|

Cornea foreign body |

9 (10.6) |

|

Cornea/corneoscleral laceration |

11 (12.9) |

|

Cornea infiltrates |

5 (5.9) |

|

Cornea ulcer |

17 (20) |

|

Hyphema |

8 (9.4) |

|

Mydriasis |

7 (8.2) |

|

Cataract |

12 (14.1) |

|

Ruptured lens |

4 (4.7) |

|

Subluxated lens |

1 (1.2) |

|

Commotio

retina |

1 (1.2) |

|

Retinal detachment |

1 (1.2) |

|

Disc edema |

1 (1.2) |

There were many more cases of closed globe injuries

(87%) in this study with the impact of trauma extending from the surrounding

eyelid to the retina. A similar finding has been reported by other authors in

other regions of the country.15,16,19 In a

study in Pakistan closed globe injuries were also reported to be commoner

accounting for 50.6% of cases.20 A possible explanation to this is

the fact that most of the agents of injuries are possibly blunt objects like

fist / finger and other non organic and organic matters. Near half (43.5%) of

the patients were blind in the affected eye at presentation while another

(9.4%) had low vision. All these patients claimed to have normal vision in the

affected eye before the injury. This reinforces the possibility of variable

effects of injuries to the globe. The effect of trauma on the eye may vary with

the agent of injury, impact site and force as well as timeliness and

appropriateness of interventional measures. It may also vary with the type and

appropriateness of protective eye device worn at the time of injury. Only one

(1.2%) of our patients was wearing a protective eye device at the time of

injury. There could also be concomitant injuries to other surrounding

structures like the face and head as

shown in our study and also in a study on maxillofacial injuries in Abuja21

Many injuries were occupationally related (44.7%) occurring either in a workshop (24.7%) or

during farmwork (20.0%). Work related eye injuries

have been found to constitute a substantial proportion of eye injuries.22,23

They are found to be largely preventable especially if adequate eye protections

are worn and appropriate guards are positioned over obvious hazards.24

Some injuries were related to leisure activities like playing (14.1%) or fighting

(17.6%) similar to the finding by Desai et al25 where they observed

that domestic and leisure activities were common causes of ocular trauma

especially in women and children. Domestic related eye injuries were however

very few (3.5%) in this study just like it constituted 4.85% (100 out of 2061)

of all ocular emergencies seen in a study in Iran.26 Contrary to a

study in another region of the country where it was reported as the commonest

cause of eye injury accounting for 55 eyes out of 230 segment examination was otherwise normal in both the eyes.

IOP was in normal limits. Pupillary reactions were normal. Right fundus was albinotic showing hypopigmentation and temporal disc pallor

and left fundus was normal (Fig. 3). Gonioscopy

revealed grade IV angle in both eyes, normal iris vessels seen in angle of

right eye.

Fig. 1: Source of referral

Fig. 2: Medications utilized

before presentation

A study in south

Nigeria reported assault as the commonest source of injury accounting for 62.2%

of cases of eye injuries.27 More than half of the patients presented

after 24 hours of injury. This shows a late pattern of presentation among our

patients. The reasons for late presentation were not determined in this study

however we discovered that many of our patients 59 (69.4%) had utilized one

form of selfcare or the other before presentation to

our centre. Top on the list of this self care materials was antibiotics in 32 (37.6%)

of the patients. Other things utilized are as shown in figure 2. This may

contribute to delayed presentation by the patients. Other factors that may

contribute to delayed presentation include awareness of existing eye care

facilities, proximity to eye care facility and cost of care. The modality of

management could vary depending on the extent and impact of trauma to the eye

as shown in our study. As shown in Table 5 the impact of trauma to the globe

were of varying extent from lid laceration (5.9%), subconjunctival

hemorrhage (15.3%) cornea affectation in 49.4%, lens affectation in 18.8% and

retina affectation (2.4%). About 32% had surgical intervention while the other

larger group were managed medically as shown above.

The determinants of modality of intervention include presence of foreign body

as well as the violation of the structural and functional integrity of the wall of the globe.

CONCLUSION

Ocular injuries are still common in our

community. The age group that are most predisposed are the

working and economically active group. Most injuries were either

occupational related or related to leisure activities like play or assault.

Many of the patients engaged in some form of self care before presentation.

Many of them presented to the clinic after 24 hours of injury with about 43.5%

presenting with blindness in the affected eye.

Authors Affiliation

Dr. Iyiade A Ajayi

Department Of Ophthalmology

University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti

Nigeria

Dr. Kayode O Ajite

Department Of Ophthalmology

University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti

Nigeria

Dr. Olusola J Omotoye

Department Of Ophthalmology

University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti

Nigeria

REFERENCES

1.

Mac Ewen C. J eye injuries: a prospective survey of 5671 cases. Br. J Ophthalmol. 1989; 73: 888-94.

2.

Nwosu SN. Blindness and visual

impairment in Anambra state Nigeria. Trop. Geogr. Med. 1994; 46: 346-9.

3.

Schein OD, Hibberd PL, Shingleton BJ, et al. Spectrum and burden of

ocular injury. Ophthalmology. 1986; 95: 300-5.

4.

Mieler WF. Ocular injuries: is it

possible to further limit the occurrence rate? Arch Ophthalmol.

2001; 119: 1712-3.

5.

Jahangir T,

Butt NH, Hamza U, et al. Pattern of presentation

and factors leading to ocular trauma. Pak J Ophthalmol.

2011; 27: 96-102.

6.

Ajaiyeoba AI. Ocular injuries in

Ibadan. Nig.J. Ophthalmol.

1995; 3: 23-25.

7.

Qureshi MB. Ocular injury pattern

in Turbat, Baluchistan, Pakistan. Comm

Eye Health. 1197; 10: 57-8.

8.

Mukherjee

AK, Saini JS, Dabrai SM. A profile of penetrating

eye injuries. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1984; 32: 269-71.

9.

Nordber E. Ocular injuries as a

public health problem in Sub-saharan Africa:

Epidemiology and prospect for control East Africa Med J 2000; 77: 1-43.

10. Castellarin AA.

Pieramici D.J Open globe Management. Compr Ophthalmol

Update. 2007; 8: 111-24.

11. Negrel AD.

Magnitude of eye injuries Worldwide. J comm. Eye Health. 1997; 10: 49-64.

12.

Schein OD, Hibberd PL, Shingleton BJ, et al. Spectrum and burden of ocular injury. Ophthalmology. 1986; 95: 300-5.

13. Otoibhi SC, Osahon AI. Perforating eye injuries in children in Benin city, Nigeria. Journal of medicine and Biomedical

research. 2003; 2: 18-24.

14. Omoti AE.

Ocular trauma in Benin city. Africa Journal of Trauma.

2004; 2: 67-71.

15. Okeigbemen VW, Osaguona VB. Seasonal variation in

ocular injury in a tertiary health center in Benin city Sahel Med J 2013; 16: 10-4.

16.

Omolase

CO, Omolade EO, Ogunleye

OT, Omolase BO, Ihemedu CO, Adeosun OAs. Pattern of ocular injury in Owo, Nigeria. Journal of ophthalmic and Vision Research.

2011; 6: 114-8.

17.

Okoye

OI. Eye injury requiring hospitalization

in Enugu Nigeria: a one year survey. Nigerian Journal of Surgical Research.

2006; 8: 34-7.

18. Ukponwan CU, Akpe AB. Aetiology

and complications of ocular trauma Nig J surgsci.

2008; 18: 92-100.

19. Bankole OO. Ocular injuries in a semiurban

Region Nig J Ophthalmol. 2003; 11: 86-9.

20. Bukhari S, Mahar PS, Qidwai

U, et al.

Ocular trauma in Children Pak J Ophthalmol. 2011; 27:

208-13.

21. Osunde OD, Omole IO, Ver-or

N, Akhiwu BI, Adebola RA, Iyogun CA, Efunkoya AA. Paediatric

maxillofacial injuries at a Nigerain teaching

hospital: A 3 year review Nigerian Journal of clinical Practice. 2013; 16:

149-54.

22. Lipscomb HJ, Dement JM,

MCDougal V, et al. Work related eye injuries among union carpenters. Appl

Occup Environ Hyg. 1999;

14: 665-76.

23. Khan MD, Kunndi N.

Mohammed Z, Nazeer A. A 61/2 years survey of

intraocular and Intraorbital foreign bodies in the

North West Frontier Province, Pakistan. Br J Ophthalmol.

1987; 71: 716-9.

24. Lipinscomb HJ. Effectiveness of intervention to prevent work

related eye injuries. Am J Prev Med. 2000; 18: 27-32.

25.

Desai P, MacEwen CJ, Baines

P, Minnaissian DC. Epidemiology and implications of ocular trauma admitted to hospital in

Scotland. J Epidemiol Comm. Health Health. 1996; 50: 436-41.

26.

Mansouri MR, Mirshahi A, Hosseini M.

Domestic ocular injuries: a case series. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007; 17: 654-9.

27.

Emem A,

Uwemedimbuk E Prevalence of traumatic ocular

injuries in a teaching hospital in South-South Nigeria- A two year review. Adv Trop Med Pub Health Int. 2012; 2: 102-8.