Corneal tattooing has been used not only as a cosmetic treatment

for corneal opacities but for optical reasons as well for centuries. A whitish

corneal scar following keratitis or trauma is cosmetically disfiguring as well

as causes scattering of light and glare. Tattooing such a cornea not only

blends the opacity to the normal eye color which is cosmetically acceptable in

a blind eye but removes the glare in a sighted eye. It has been recommended to

improve the sight of an eye in cases of albinism,

aniridia,

coloboma,

iridodialysis,

keratoconus

or diffused nebulae of the cornea.1,2 In these situations, it

reduces the symptomatic glare associated with a dysfunctional pupil or

scattering of light produced by corneal opacities.

Various methods have been introduced and modified over the years.

Galen (131-210 A.D.)3 is considered to be

the first who dyed human cornea to mask a corneal opacity using reduced copper sulphate. Then Louis Von Wecker4, an oculoplastic surgeon in 1869, used black India ink

to tattoo a leucoma of the eye. He anesthetized the

eye with cocaine and covered the cornea with a thick solution of ink. The

pigment was then inserted into the corneal tissue with a grooved needle

obliquely. In 1901, Nieden5 used an electric tattooing needle based

upon the idea of a fountain pen. Another physician, Armaignac5, used

a small funnel fixed to the cornea by three small points. China ink was filled

into the instrument and injected into the stroma with

a needle. Nowadays, two methods are used predominantly for tattooing the

cornea.

(1) Chemical Method:

this involves using metallic salts which react with each other chemically to

produce a brown-black precipitate that is taken up by the keratocytes

and stain the cornea. The chemicals used are Gold chloride, platinum chloride,

silver nitrate reduced by hydrazine hydrate to a black pigment. The reacting

chemicals are applied over the stroma directly after

peeling the corneal epithelium. This technique was first introduced by Arif O Khan and David Meyer6.

(2) Coloring Method: this technique involves the direct

introduction/impregnation of colored pigments into the corneal stroma. To obtain a

uniform color, the dyeing agent is injected through multiple micro-punctures7

by a needle inserted into the corneal stroma. Various

colored dyes and inks such as Indian ink, organic colors, animal uveal pigment, Chinese ink, soot have been used. To obtain

different shades, surgeons experiment with different combinations of such

chemical products.

The new

advances in technology include using excimer laser to

prepare the corneal bed for tattooing8; lamellar keratectomy offers excellent results in terms of a

homogeneous application of colour9 but for many scars, this is not possible because of irregularity,

thinning, staphyloma or calcification of cornea.

Penetrating keratoplasty (PK) has the risks of

infection and graft rejection and its use for cosmetic purposes is ethically

unacceptable in many parts of the world due to the worldwide shortage of corneal

donors. Mechanized keratopigmentation10 is another costly option.

Alternative methods to improve the aesthetic appearance of disfigured eyes are

cosmetic contact lenses, keratoplasty, wearing ocular

prosthesis with or without an enucleation or evisceration11.

With contact lenses, intolerance frequently develops after prolonged use12

while wearing an ocular prosthesis over a scarred cornea often causes

inflammation, infection and corneal erosion. Hence tattooing of corneal

opacities still has a role for the cosmetic improvement of unsightly corneal

scars. Our study aimed to investigate the potential of corneal tattooing to

improve the ocular cosmetic appearance, to demonstrate its safety, efficacy and

to investigate its potential as an alternative to invasive reconstructive

surgery for the cosmetic correction of disfigured corneas.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This

prospective, interventional, non-comparative clinical case study was conducted

at the oculoplastic department of Mughal Eye Trust

Hospital, Lahore, a tertiary care referral centre, from June 2012-Dec 2013. 44

consecutive, non randomized patients were included in the study between the age

range of 5 – 60 years (median 21 years). There were 19

females (43.18%) and 25 males (56.82%). All of them were blind in one eye due

to past trauma and desired a cosmetic treatment for their disfigured, white

eye. Ophthalmic examination was performed thoroughly including B scan

ultrasound to exclude intraocular tumor. The depth of corneal opacity, corneal

thickness, the presence and extent of band keratopathy

and corneal vascularization was carefully assessed by biomicroscopy.

Study inclusion criteria was superficial or deep

corneal opacities, band keratopathy, leukokoria (due to a dense cataract with no visual potential

or a pupillary membrane). Patients with phthisical

eyes, thin corneas, corneal edema (bullous keratopathy),

anterior staphyloma and glaucoma were excluded from

the study.

After

fully explaining to the patients and their parents that this procedure was not

meant to restore sight but only their cosmetic appearance and they may need a

repeat procedure, an informed consent was obtained and preoperative photographs

of the patients’ eyes were taken. Corneal tattooing was performed under general

anesthesia in children and local anesthesia (retrobulbar)

in adults. Accurate measurement of corneal area to be tattooed compared to the

second eye was done intra-operatively with a caliper. Corneal epithelium was

debrided using a No.15

Bard Parker-knife. In eyes with band keratopathy (12

cases), first chelation was performed with EDTA solution applied with a cotton

wick on the debrided cornea for 10 minutes. It was then washed off with normal

saline. Any bleeding corneal vessels were cauterized at the limbus.

After drying the cornea with a sponge, 2% Gold Chloride solution was applied

over the corneal stroma and left for two minutes;

then 2% Hydrazine Hydrate solution was applied over the stroma

painted with gold chloride. A black precipitate immediately formed (due to a chemical

reaction between the two solutions) which deeply stained the stroma. It was left in place for 25 seconds and then washed

off with normal saline. Atropine eye drops (1%) and tobramycin eye ointment

were instilled and a pressure dressing was done with a double eye-pad for 24

hour. Postoperatively, all cases were given NSAIDS orally for two days. The

dressing was removed the next morning and Diclofenac

Sodium eye drops were prescribed four times / day, atropine 1% eye drops twice / day and

antibiotic eye drops four times /day for a week. Patients were followed up at

the first, third and fifth post-operative day; then weekly for a period of 1

month and then at 3rd month, 6th month and 1st year post-operatively.

RESULTS

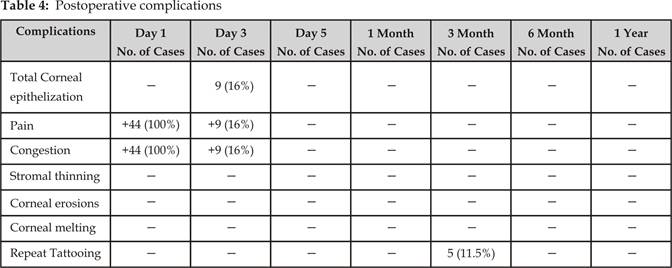

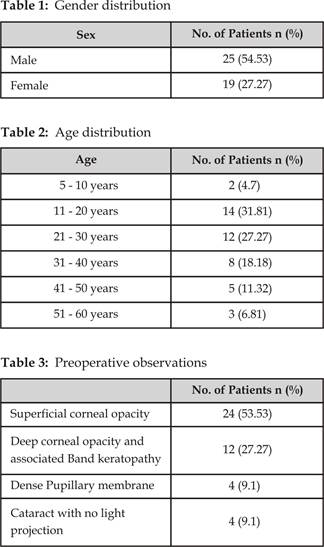

Forty four eyes of 44 patients,

19 females (43.18%) and 25 males (56.82%), (Table 1), with an age range of 5 to

60 years (Table 2) underwent corneal tattooing for disfiguring corneal scars (Table 3). 24 cases

(54.53%) had superficial corneal opacities, 12 cases (27.27%) had deep corneal

opacities with associated band keratopathy. A dense

pupillary membrane with clear cornea was present in 4 cases (9.1%) while a

cataract with no visual potential and an associated corneal opacity was present

in 4 cases (9.1%).

On the first postoperative day

(Table 4), 96% of the patients complained of a moderate foreign body sensation

and exhibited a conjunctival injection which

corresponded to the surgically induced corneal epithelial defect and chemical

reaction. Once the cornea was completely epitheliazed

in 48 hours in 37 cases (84%) and after 5 days in 7 cases (16%), the discomfort

and conjunctival injection resolved. Corneal

infection was not observed in any case. Minimal pigment loss was observed in 5

cases (11.5%) from 3 month onwards and they underwent a repeat procedure.

Corneal melting and corneal erosions were not seen in any case. One year

postoperatively, 42 cases (95.5%) were satisfied with the cosmetic appearance

and were asymptomatic; 2 cases (4.5%) were lost to follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Several

methods for corneal tattooing are in practice today with varying opinions

regarding their safety and success. Chemical tattooing as described in this

study involves a chemical reaction where gold chloride is reduced by hydrazine

hydrate to a black precipitate7. This

metallic precipitate is deposited in the keratocytes

and between the stromal lamellae from which it slowly migrates into the

regenerated epithelium and stays there for a variable time period. It is

important that the bowman's membrane is not damaged during the procedure as its

integrity is very essential for maintaining a strong and healthy epithelial

lining of the cornea. Injury to this membrane either mechanically while

performing epithelial debridement or chemically results in recurrent corneal

erosions which is an intractable and painful condition14. In our

technique, the epithelium was carefully removed under the microscope without

damaging the Bowman's membrane. This gave 95% satisfactory results to our

patients with no corneal erosion seen in any case during follow up.

On the other hand, the method

of direct impregnation of colored dyes

either by a needle or a blade is not 100% safe12. It is very

difficult to determine the exact depth the needle or the blade has traversed

through an opaque cornea and accidental damage to the Bowman's membrane can

easily occur particularly when multiple needle punctures are made. The corneal

epithelium fails to adhere and stabilize at the site where Bowman's membrane is

damaged. Hence the problem of recurrent corneal erosions is frequently seen

because of this technique. Moreover, there is always a risk of accidently

puncturing the cornea at the area of stromal thinning when corneal punctures

are made blindly at multiple sites by a needle. This complication was easily

avoided by our technique.