Original Article

Congenital

Cataracts; Its Laterality and Association with Consanguinity

Afia Matloob Rana,

Ali Raza, Waseem Akhter

Pak J Ophthalmol 2014, Vol. 30

No. 4

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.. . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . .

|

See end of article for authors affiliations

..

.. Correspondence to: Afia Matloob Rana

Ophthalmology Department Holy Family Hospital, Rawalpindi Satellite Town, Rawalpindi Email: afiamatloob@yahoo.com

..

.. |

Purpose:

To study the frequency of laterality (bilateral vs. unilateral) and its

importance among congenital cataracts. We also investigated

consanguinity as a risk factor in congenital cataract cases. Material

and Methods: This study was

conducted in Ophthalmology department, Holy

family hospital, Rawalpindi, from 2nd January 2013 to 2nd

February 2014. A total of 112 eyes

and 86 patients in age range from 3 months to 26 years and all types of

visually significant congenital cataracts total or partial without prior history

of ocular trauma and syndromic association were recruited for the study.

Frequency distribution, test of significance was carried out using

Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 20.0. Results: A total of 112 cases (61 males, 51 females) were recruited in the study. There was no statistically significant difference between different age groups and gender (p=0.2). The unilateral cases were 19.6% and bilateral were 80.4%. Consanguinity was present in 69.6% (n=78) and absent in 30.4% (n=34). The difference was statistically significant (p=0.00). Conclusion:

Bilateral congenital cataract is a more common

presentation as compared to unilateral cataract. Consanguinity is an

important risk factor for congenital cataract especially bilateral cataracts. Key Words: Congenital Cataracts; ocular trauma, Syndromic association |

Congenital cataract is an

important cause of preventable visual deprivation in children accounting for

5%-20% of blindness in children worldwide.1,2 World wide, the

number of children who are blind is estimated to be 1.4 million, 190,000 of

them from cataract.3 Cataract in children can be classified as

congenital, developmental or traumatic.4

Congenital cataract presents

either from birth or shortly thereafter, while developmental cataract usually

refers to cataract that appears after the age of two5. Pediatric

cataracts are responsible for more than 1 million childhood blindness in Asia.6

The prevalence of cataract in children has been estimated about 3 in 10,000

live births.7 Ocular morbidity is mainly caused by obstruction to

development of the visual system and it has great physical, social economical

and psychological impact.

Prevention of visual

impairment and blindness in childhood due to congenital and infantile cataract

is an important international goal4 and is a priority for vision

2020.8 Epidemiology of congenital cataract is not fully understood

because its not a specific entity but combination of multiple factors,

including many associated ocular pathologies.

Density and laterality of

congenital cataract are one of the most important parameters in terms of visual

outcome, others are type of cataract, associated

ocular pathology and delay in presentation to hospital. Unilateral dense

cataract is a definite indication for early cataract surgery (preferably within

days) which is followed by aggressive amblyopia treatment, even then the

results mostly remain poor.9 Unilateral cataracts are generally

sporadic, with no family history of cataract or systemic illness, and affected

infants have history of full-term and normal health.9

Genesis of congenital cataract

is still not explored well and very little is known because of modern techniques,

long term accurate data needed and lack of sensitive investigative procedures.

Genetic factors are important in the etiology of congenital cataract, up to

half of childhood cataracts are genetic in origin10. Nearly,

one-third of total congenital cataract cases are familial.11 These types of cases are mainly because of genetically

induced developmental alterations among the crystalline lens and surrounding

tissues. There are a lot of ongoing epidemiological studies to find out risk

factors like intrauterine infections, certain enzymes deficiency, and sporadic.

The knowledge about the causes is important to develop appropriate planning

strategies, which are not available for many regions of the world and where

these are available, has been obtained mostly from studies of selected

populations, or from routine sources which are often based on small numbers of

cases.12

Routine ocular examination of young infants is

widely recommended to ensure that treatment, genetic counseling, and other

advice and support are offered at the earliest opportunity. The parents and any

siblings should be examined thoroughly even in the absence of positive family

history. In this study we are trying to analyse

frequency of laterality among congenital cataract and to investigate

consanguinity as risk factor among hospital data of congenital cataract in

patients attending our ophthalmology department.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Our study includes patients

with congenital / infantile cataract presenting to Ophthalmology department, Holy

family hospital, newly diagnosed during the 12-month period from 2nd

January 2013 to 2nd February 2014 identified prospectively. It

include 112 eyes and 86 patients in age ranging from 3 months to 26 years and

including all types of visually significant cataracts total or partial without

prior history of ocular trauma and syndromic

association. All affected individuals underwent a detailed history and

ophthalmological examination. Morphological details of cataract including other

ocular associations and also detailed dilated fundus examination where possible

were recorded. Informed consent was obtained and detailed medical and family

history with especial emphasis on consanguinity was obtained by taking detailed

history from parents or guardian of children on admission using a standardized

questionnaire. Ophthalmic examination included assessment of the pupillary red

reflex with a direct ophthalmoscope, visual acuity or fixation and following

behavior checked according to age of patients, complete anterior segment

examination with slit lamp and retinoscopy was done, B-scan was also done where required. All patients

underwent irrigation and aspiration of cataract with or without IOL followed by

aphakic correction where required according to latest

recommendations. Laterality and association of consanguinity with congenital

cataract was noted and assessed.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical

Package for Social Sciences Version 20. Fisher exact test was performed to

determine statistically significant differences in the gender of the

population. A p value of <0.05 was taken to be significant in all analysis.

RESULTS

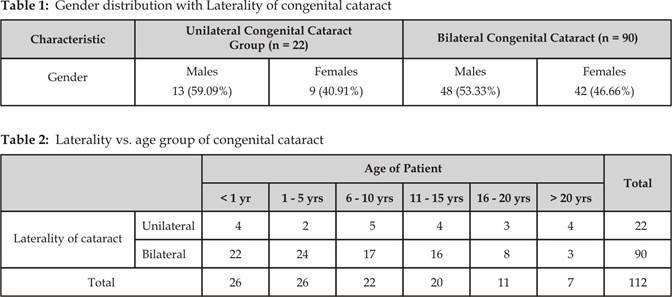

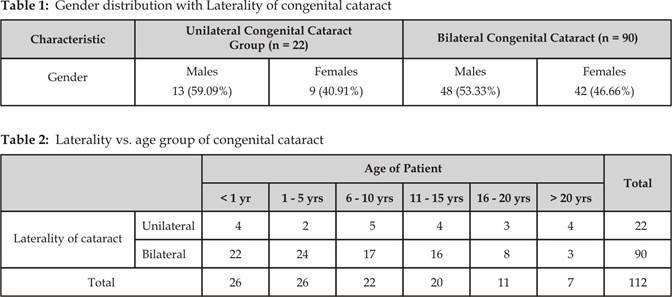

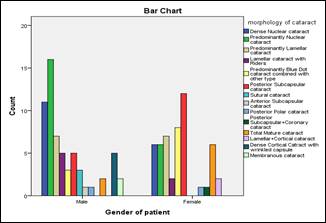

Congenital cataract characteristics and demographics of

the cases are shown in table 1 while table 2 shows laterality with age distribution,

picture 1 showing consanguinity with laterality while picture 2 showing

different morphological presentations of congenital cataract with gender

distribution.

A total of 112 cases (61 males, 51 females) were recruited

in the study. The distribution of congenital cataract cases for different age

groups in our study was as follows for less than 1 year age group 24.4% (n=15

males, n=11 females), age group 15 years 25% (n=19 males, n=7 females), age

group 610 years 19.6% (n=12 males, n=10 females), age group 1115 years 17.9%

(n=8 males, n=12 females), age group 1620 years 9.8% (n=4 males, n=7 females)

and age group more than 20 years 6.3% (n=3 males, n=4 females). There was no

statistically significant difference between different age groups and gender

(p=0.2). The bilateral cataracts (n=90) included 48 (53.33%) males

and 42 (46.66%) females, while unilateral cataract (n=22) comprised of 13

(59.09%) male and 9 (40.91%) female cases. In both bilateral and

unilateral cataract groups males were more as compare to females. This

difference was not statistically significant (p=0.093).

The cumulative unilateral cases were 19.6% and bilateral were 80.4%. In age

group less than 1 year 18% were unilateral and 24% were bilateral, in group 1-5

years unilateral were 9% and bilateral were 26%, in age group 6-10 years

unilateral was 23% and bilateral were 18%, in age group 11-15 years unilateral

were 18% and bilateral were 18%, in age group 16 20 years unilateral were 14%

and bilateral were 9%, in age group more than 20 years unilateral were 18% and

Fig. 1:

Fig.

2:

bilateral were 3%, there was no statistical significance (p=0.093) between age of presentation of congenital cataract

and laterality.

Consanguinity was present in 69.6% (n=78) and absent in

30.4% (n=34). The difference was statistically significant (p=0.00). Out of total cases with positive consanguinity 18%

(n=14) were unilateral and 82% (n=64) were bilateral while with absent

consanguinity 24% (n=8) were unilateral and 76% (n=26) were bilateral. There

was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p=0.49).

In our study we also observed different morphologies of

cataracts. The frequencies of different types of congenital cataract were;

dense nuclear cataract 15.2% (n=11 males, n=6 females), predominantly nuclear

cataract 19.6% (n=16 males, n=6 females), predominantly lamellar cataract 12.5%

(n=7 males, n=7 females), lamellar cataract with riders 6.3% (n=5 males, n=2

females) f, predominantly blue dot cataract 9.8% (n=3 males, n=8 females),

posterior sub-capsular cataract 15.2% (n=5 males, n=12 females), sutural cataract 2.7% (n=3 males, n=0 females), anterior

sub-capsular cataract 0.9% (n=1 males, n=0 females), posterior polar 1.8% (n=1 males, n=1 females) , sub-capsular

coronary cataract 0.9% (n=0 males, n=1

females) , total mature cataract 7.1% (n=2 males,

n=6 females), cortical cataract 1.8% (n=0 males, n=2

females) , cortical cataract with wrinkle 4.5% (n=5

males, n=0 females), and membranous cataract 1.8% (n=2 males,

n=0 females). There was statistically significant difference between

gender and morphology of cataract (p =0.01).

DISCUSSION

Congenital cataract is a major cause of blindness in children. Congenital cataract is important in the regards that it blurs the retinal image as well as disrupts the development of the visual pathways in the central nervous system. Congenital cataract is a rare disease, but it is a major cause of low vision or blindness among both developed13 and developing14 countries. The causes for most of the congenital cataracts remained unknown.15,16 Prevention of visual impairment due to congenital and infantile cataract is an important component of world health organizations international program for elimination of avoidable blindness by 202017. Surgical removal of the opacified lens with and without intraocular lens implantation is the only treatment available for congenital cataract.18

In our study male were 55%

(n=61) and females were 45% (n=51). Male to female ratio was similar to the

study of Mwende J et all19,

who had 55% (n=99) males and 45% (n=81). In the same study bilateral cataracts

were 66% and unilateral were 34%, while in our study it was 80.4% and 19.6%

respectively. Rahi JS et all20.

In their study also the same ratio of laterality 66% and 34% was observed

respectively. The difference was not statistically significant in both studies.

The difference between our study and the two groups was because of the included

age group which was more in our study from 3 month to 26 years while in the

rest of the two studies it was 1 year of age. Ruddle

JB et al,21 also observed in their study

that there was no significant difference between laterality of cataract

(bilateral 45.5% vs. unilateral 55.5%) or gender (p = 0.068). Laterality is one of

the most important parameters in terms of management. Unilateral cataracts have

poor prognosis as there are much more chances of amblyopia as compare to

bilateral. In unilateral congenital cataract prognosis for visual outcome after

cataract surgery depends on early clearance of visual axis, aphakic

correction, and aggressive amblyopia treatment. Congenital cataracts ideally

should be operated before three months of age.19

In our study cases presented

before one year of age group was 24.4% including 18% unilateral and 24%

bilateral. After one year of age 75.6% cases presented including 82% unilateral

and 76% bilateral. As we observed in our study that small number of cases

presented before one year of age and unilateral cataracts were less in numbers.

The reason was the early appreciation of reduced vision in bilateral cases.

Management of congenital cataract depends on the etiology, degree of visual

interference and laterality of cataract. The outcome of cataract surgery after

congenital cataract is 20 times worse than developmental cataracts, especially

for those cases which are operated after one year of age.22 The

visual system can get the opportunity to develop and mature after surgery while

its progress remains halted by the development of cataract and visual system

cannot develop at all in presence of dense congenital cataract 23.

Thats why early cataract surgery is important in congenital cataract.

Especially for severe bilateral cataracts which are causing significant

obscuration of the visual axis, surgery is recommended as early as possible.

In developing countries delay

in presentation and inadequate use of surgical services are the major causes of

blindness secondary to congenital cataract24. The visual outcome depends

upon the duration between onset of visual impairment and surgery, the shorter

the duration, higher likelihood of good visual outcome. Early presentation is

important for visual outcome, regardless the type of cataract. The reasons of

excessive delay of presentation in our study population were few barriers to

presentation, which include lack of awareness about the disease, difficult

access to health services, or acceptance of services (lack of education).

In the language of clinical

genetics, a consanguineous marriage is defined as a union between two

individuals who are related to each other as second cousins or closer, with the

inbreeding coefficient (F) equal or higher than 0.0156, where (F) is a measure

of proportion of loci at which the offspring is expected to inherit identical

gene copies from both partners. Among Arabs and south Indian communities the

inbreeding coefficient (F) is highest where it reaches up to 0.125.25

In our study we observed

statistically significant high rate of positive history of first cousin

marriage and among the positive cases bilateral cataracts were more common as

compare to unilateral cataracts. This high rate of observed consanguinity may

be considered as one of the risk factor for congenital cataract. At the same time

this aspect could not be overlooked that consanguinity is very common in

Pakistani families and this relationship of consanguinity with congenital

cataract as risk factor may be an incidental finding as number of our patients

were limited.

A significant positive

association has been consistently demonstrated between consanguinity and

morbidity, although consanguinity associated blindness is less frequent but an

increased rate of congenital cataracts has been reported in several

populations.26 One billion people are currently living in those

countries where consanguineous marriages are customary, and among them, one in

every three marriages is cousin marriage, with a deeply rooted social trend.

Public awareness is rising about preventive measures of congenital disorders

which has led to a trend that the number of couples who are seeking for

preconception and premarital counseling on consanguinity are increasing

gradually.27

The morphology of congenital

cataracts is also very helpful in establishing their etiology and prognosis.

Congenital cataract is inherited in all three Mendelian

forms: autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked. In view of

association of congenital cataract with consanguinity in literature, and the

need to identify and delineate the variability in congenital cataract, the

present study was undertaken to ascertain the role of consanguinity in

congenital cataract patients.

The prospective study of laterality and

consanguinity in congenital cataract has several limitations. Although we

believe that all patients included in our study had congenital cataract not all

patients were seen from time of birth .These cataracts showed many different

patterns. The underlying and associated factors in patients with congenital

cataract in this study were diverse. This complex pattern including variable

differences between unilateral and bilateral cataracts has implication for

further etiological research.

CONCLUSION

Bilateral congenital cataract is a more common presentation

as compare to unilateral congenital cataract..

Consanguinity is an important risk factor for congenital cataract especially

for bilateral cataracts.

Authors Affiliation

Dr. Afia

Matloob Rana

Post Graduate Resident

Ophthalmology Department

Holy Family Hospital

Rawalpindi

Dr. Ali Raza

Associate Professor

Ophthalmology Department

Holy Family Hospital

Rawalpindi

Dr. Waseem

Akhter

Assistant Professor

Ophthalmology Department

Rawal Institute of Health Sciences

Islamabad

REFERENCES

1.

Halilbasic M, Zvornicanin J, Jusufovic V, Cabric E, Halilbasic A, Musanovic Z, Mededovic A. Pediatric cataract in Tuzla Canton, Bosnia and

Herzegovina. Med Glas (Zenica)

2014; 11:127-31.

2.

Santhiya ST, Kumar GS, Sudhakar

P, Gupta N, Klopp N, Illig

T, Sφker T, Groth M, Platzer M, Gopinath PM, Graw J. Molecular analysis of cataract families in India: new mutations

in the CRYBB2 and GJA3 genes and rare polymorphisms. Mol Vis. 2010; 16:

1837-47.

3.

Randrianotahina HC, Nkumbe HE. Pediatric cataract surgery in Madagascar. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014; 17:14-7.

4.

Nkumbe HE, Randrianotahina HC. Meeting the need for

childhood cataract surgical services in Madagascar. Afr

J Paediatr Surg. 2011; 8:182-4.

5.

Bronsard A, Geneau R, Shirima S, Courtright P, Mwende J. Why are children brought late for cataract surgery? Qualitative

findings from Tanzania. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;

15: 383-8.

6.

World Health Organisation. Prevention of

childhood blindness. Geneva: WHO; 1992.

7.

Sana N, Muhammad A, Humaira F. Congenital Cataract:

Morphology and Management Pak J Ophthalmol. 2013; 29:

151-55.

8.

Global Initiative for the Elimination of Avoidable Blindness:

Action Plan. 2006-2011. 2007.

9.

Tuli SY, Giordano BP, Kelly M, Fillipps

D, Tuli SS. Newborn with an Absent Red Reflex. J Pediatr Health Care. 2013; 27: 515.

10.

Haiba KS. Amer R, Mariam S, Samra K, Nadeem HB, Ahmed UZ. Autosomal recessive

congenital cataract linked to EPHA2 in a consanguineous Pakistani family. Mol

Vis. 2010; 16: 511-17.

11.

Jochen G. Congenital hereditary cataracts, Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004; 48:

1031-44.

12.

Jugnoo SR, Carol D. The British Congenital Cataract Interest Group

Congenital and Infantile Cataract in the United Kingdom: Underlying or

Associated Factors Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.

2000; 41: 2108-14.

13.

Rosenberg T. Yearly Memorandum from the Danish National Register of the

Visually Impaired. 2002; 14.

14.

Ezegwui IR, Umeh RE, Ezepue UF. Causes of childhood blindness: results from schools for the blind

in south eastern Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003; 87:

203.

15.

Bhatti TR, Dott M, Yoon PW,

Moore CA, Gambrell D, Rasmussen SA. Descriptive epidemiology of

infantile cataracts in metropolitan Atlanta, GA, 19681998. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003; 157:

3417.

16.

Haargaard B, Wohlfahrt J, Fledelius H, Rosenberg T, Melbye

M. A nationwide Danish study of

1027 cases of congenital/infantile cataracts: etiological and clinical

classifications. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111: 22928.

17.

Courtright P, Hutchinson AK, Lewallen

S. Visual impairment in children

in middle- and lower-income countries. Arch Dis Child. 2011; 96: 1129-34.

18.

Yorston D. Surgery for Congenital Cataract. Community eye health. 2004; 17:

23-5.

19.

Mwende J, Bronsard A, Mosha M, Bowman R, Geneau R, Courtright P. Delay in presentation to hospital for surgery for congenital and

developmental cataract in Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol.

2005; 89: 147882.

20.

Rahi JS, Dezateux C. Congenital and Infantile

Cataract in the United Kingdom: Underlying or Associated Factors. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000; 41: 2108-14.

21.

Ruddle JB, Staffieri SE, Crowston JG, Sherwin JC, Mackey DA. Incidence and predictors of

glaucoma following surgery for congenital cataract in the first year of life in

Victoria, Australia. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013; 41: 653-61.

22.

Magnusson G, Abrahamsson M, Sjostrand J. Changes in visual acuity from 4 to 12 years of age in children

operated for bilateral congenital cataracts. Br J Ophthalmol.

2002; 86: 1385-9.

23.

Khanna RC, Foster A, Gogate PM. Visual outcomes of bilateral congenital and developmental cataracts

in young children in south India and causes of poor outcome. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013; 61: 65-70.

24.

Waddel KM. Childhood blindness and low vision in Uganda. Eye. 1998; 12:

18492.

25.

Hamamy H, Antonarakis SE, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Temtamy S, Romeo G, Kate LP. Consanguineous marriages, pearls and perils:

Geneva International Consanguinity Workshop report. Genet Med. 2011; 13:841-47.

26.

Bittles AH, Black ML. The impact of consanguinity on neonatal and infant

health. Early Hum Dev. 2010; 86:737-41.

27.

Hamamy H. Consanguineous marriages. J Community Genet. 2012; 3:185-92.